On the way down to Ross-On-Wye from Ludlow on our recent road trip, we decided to make a stop at the little Norman church of Kilpeck near Hereford. The church at Kilpeck is famous for its rich Norman decoration and unusual carvings, which look like they were carved only yesterday. What we didn’t know was that there was the remains of a Norman mott and bailey castle directly behind the church. We climbed up the mott to look at the small remaining section of the castle wall only to find that it had a fireplace and a section of chimney remaining in it. This chimney must be of some age as the castle and indeed the medieval town of Kilpeck fell had gone into decline prior to the black death (1348) and into disuse thereafter.

I have gleaned the following from the internet:

Kilpeck Church

The Church of St Mary and St David is a Church of England parish church at Kilpeck in the English county of Herefordshire, about 5 miles from the border with Monmouthshire, Wales. Pevsner describes Kilpeck as “one of the most perfect Norman churches in England”. Famous for its stone carvings, the church is a Grade I listed building.

The church was built around 1140, and almost certainly before 1143 when it was given to the Abbey of Gloucester. It may have replaced an earlier Saxon church at the same site, and the oval raised form of the churchyard is typical of even older Celtic foundations. Around the 6th and 7th centuries the Kilpeck (Welsh: Llanddewi Cil Peddeg) area was within the British kingdom of Ergyng, which maintained Christian traditions dating back to the late Roman period. The possibility of the site holding Roman and even megalithic remains has been raised, but is unproven.

The plan of the church, with a nave, chancel, and semicircular apse, is typical for the time of its construction, the Norman period. It was originally dedicated to a St David, probably a local Celtic holy man, and later acquired an additional dedication to Mary from the chapel at Kilpeck Castle after it had fallen into disrepair. At the time the current church was built, the area around Kilpeck, known as Archenfield, was relatively prosperous and strategically important, in the heart of the Welsh Marches. The economic decline of the area after the 14th century may have helped preserve features which would have been removed elsewhere. However, it is unclear why the carvings were not defaced by Puritans in the 17th century. The church was substantially repaired in 1864, 1898 and 1962, and its unique features were protected and maintained. Pevsner describes the Victorian restorations, firstly by Lewis Nockalls Cottingham and latterly by John Pollard Seddon as “competent [and] disciplined”.

The carvings in the local red sandstone are remarkable for their number and their fine state of preservation, particularly round the south door, the west window, and along a row of corbels which run right around the exterior of the church under the eaves. The carvings are all original and in their original positions. They have been attributed to a Herefordshire School of stonemasons, probably local but who may have been instructed by master masons recruited in France by Oliver de Merlimond. He was steward to the Lord of Wigmore, Hugh Mortimer, who went on a pilgrimage to Santiago de Compostela in Spain and, on his return, built a church with similar Romanesque carvings (now largely lost) at Shobdon, 30 miles north of Kilpeck. Hugh de Kilpeck, a relative of Earl Mortimer, employed the same builders at Kilpeck, and their work is also known at Leominster, Rowlestone and elsewhere. The writer Simon Jenkins notes the influences of churches found on the pilgrimage routes of Northern Europe.

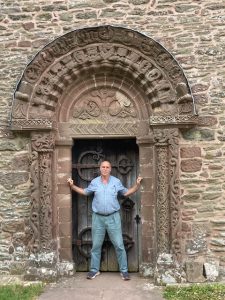

The south door has double columns. The outer columns have carvings of a series of snakes, heads swallowing tails. In common with most of the other carvings, the meaning of these is unclear, but they may represent rebirth via the snake’s seasonal sloughing of its skin. The inner right column shows birds in foliage; at the top of the right columns is a green man. The inner left column has two warriors who, unusually, are in loose trousers. The outer sections of the arch above the doorway show creatures which can be interpreted as a manticore and a basilisk, and various other mythical and actual birds and beasts. The semicircular tympanum depicts a tree of life.

Kilpeck Castle

Kilpeck Castle, immediately west of the church, consists of a motte and bailey and various outworks. The motte is roughly circular with a diameter of 54 yards at the base and a maximum height of 27 ft. above the bottom of the ditch. It is surmounted by the remains of a polygonal shell-keep of masonry of which two large fragments remain towards the north and the southwest. The keep is probably of the 12th century and was polygonal both within and without; the external faces appear to have averaged about 14 ft. and the external diameter of the building was about 100 ft. In the North fragment of walling is a fireplace-recess with a segmental back of ashlar and a round flue; to the east are remains of a cross-wall, and there are two round drain-holes piercing the outer wall. The southwest fragment has remains of an ashlar-faced oven with the springing of an arch across the front; this oven was in the angle of a cross-wall and farther north is a third drain-hole. The motte is surrounded by a ditch which separates it from the kidney-shaped inner bailey on the east and from an outer bank on the west. The bailey has an outer ditch and remains of a rampart at the north and south ends; there are slight traces of a causeway leading to the motte. The bailey was entered from the southwest, where a gap in the rampart is flanked on one side by a small mound, perhaps covering the remains of part of a gatehouse. There are three outer enclosures on the northwest and south of the main earthwork, which are of irregular form and enclosed by ditches or scarps. The stream, to the west of the site was dammed at a point level with the north side of the west enclosure. To the northeast of the main earthwork is a roughly rectangular village-enclosure, about 300 yards by 200 yards; within it stand the church and other buildings, and there are scarps on the three outer sides and remains of a rampart on the northwest and southeast sides in addition. Within the enclosure are traces of foundations at right angles to the sides. Condition of earthworks, fairly good. The castle is thought to have been first built around 1090 as the administrative centre of Archenfield.

My name is Paddy McKeown, I am a retired police officer (Detective Sergeant – Metropolitan Police), turned chimney sweep. I have completed training with ‘The Guild of Master Chimney Sweeps’, and Rod Tech UK (Power Sweeping).

My name is Paddy McKeown, I am a retired police officer (Detective Sergeant – Metropolitan Police), turned chimney sweep. I have completed training with ‘The Guild of Master Chimney Sweeps’, and Rod Tech UK (Power Sweeping).

Comments are closed.